In Brief

Conservation Value:

Kayapo Indigenous Territories are of high conservation significance because they are large enough to protect ecological processes and the full suite of southeastern Amazonian biodiversity. (See Conservation Significance section of "In More Depth", below.) They also furnish huge climate benefits.

Threats:

Kayapo lands are located in the midst of one of the world’s highest deforestation regions — an agricultural frontier with an expanding road network and little if law enforcement. Kayapo have fiercely protected their vast territory but face increased pressure from illegal incursions for goldmining, logging, commercial fishing, and ranching.

Actions & Results:

- Provisioning, organizing and other assistance has enabled greatly increased surveillance and territorial control. While surveillance and protection need further enhancement, our help has undoubtedly prevented widespread invasions of Kayapo lands. See first "In More Depth" section below re evidence of our success.

- In just a few years, Kayapo NGOs have developed the capacity for managing complex programs. Local capacity for long-term management and protection has developed well and will continue to evolve. The Kayapo have gained much greater insight into the threats they face and development options for a sustainable future.

- Sustainable and culturally compatible economic activities have been developed so the Kayapo may earn cash to buy the manufactured goods they have come to need. Brazil nut sales have been especially successful; cumaru seeds (for the cosmetics industry), bead handicrafts and catch-release-sport-fishing (see Untamed Angling; Kendjam Lodge; Xingu Lodge) are also proving to be lucrative sustainable micro-enterprises for Kayapo communities

- Discover more about this project on our dedicated project website.

Drag slider to compare 30 years of forest cover loss:

Goal:

To empower the Kayapo indigenous people to continue to protect over nine million hectares of their lands from degradation and deforestation, and to build the capacity of Kayapo NGOs to manage territorial surveillance and sustainable economic activities.

Support this projectLocation:

Southeastern Amazon, Brazil

Size of Area Involved:

9 million hectares (90,000 km2; larger than almost half of the world's countries; almost twice the size of Nova Scotia; about the size of Iceland and of South Korea)

Project Field Partner:

Associação Floresta Protegida, Instituto Kabu and Instituto Raoni

Our Investment to Date:

Cost to ICFC (2007-2024): CA$21,842,770

Special thanks to the the following for their strong support for this project: 1994 Fund, Environmental Defense Fund, International Conservation Fund, Paul W. O'Leary Foundation, Global Wildlife Conservation, Schmidt Family Foundation, Sarah & Cary Lavine Family Foundation, The A Team Foundation, Naia Trust, Red Butterfly Foundation, CarbonFlip Fund, and the Zita and Mark Bernstein Family Foundation, as well as individual donors. Other major funders (not through ICFC) are the Amazon Fund and the Kayapó Fund.

Gallery

Click to enlarge an image

Video

In More Depth...

The overarching goal of the Kayapo-conservation NGO alliance is to empower the Kayapo to defend their constitutional rights, protect their ecologically intact territories and develop sustainable economic autonomy within the lawless frontier zone of the southeastern Amazon. The Kayapo entered into alliances with outside NGOs to obtain the help they needed to protect their constitutional right to exclusive occupation and control over their territory and, indeed, their very survival. Once they gain a foothold, loggers and goldminers quickly overwhelm Kayapo traditional governance systems and overtake an area. The eastern Kayapo were drawn into the illicit frontier economy in the 1980s and 1990s having had no experience with these activities and no support to develop economic alternatives or to foresee the inevitable and irreversibly destructive consequences of predatory logging and goldmining. Immersed in a region where lawlessness and corruption prevail, they have lost control over roughly 1.2 million hectares of their territory in the east, which is now a no-man’s land dominated by goldminers, loggers and other illegal actors. The Kayapo living in these eastern communities depend on these actors for outside goods. Most rivers in this area are choked with mud and polluted by mercury used in goldmining. Forest is degraded by logging which removes most of the big, old growth primary forest trees so pivotal to the overall ecology of this biome. This opens these once resilient forests to fire. Traditional culture breaks down in lockstep with environmental degradation and the introduction by loggers and miners of alcohol, drugs and prostitution.

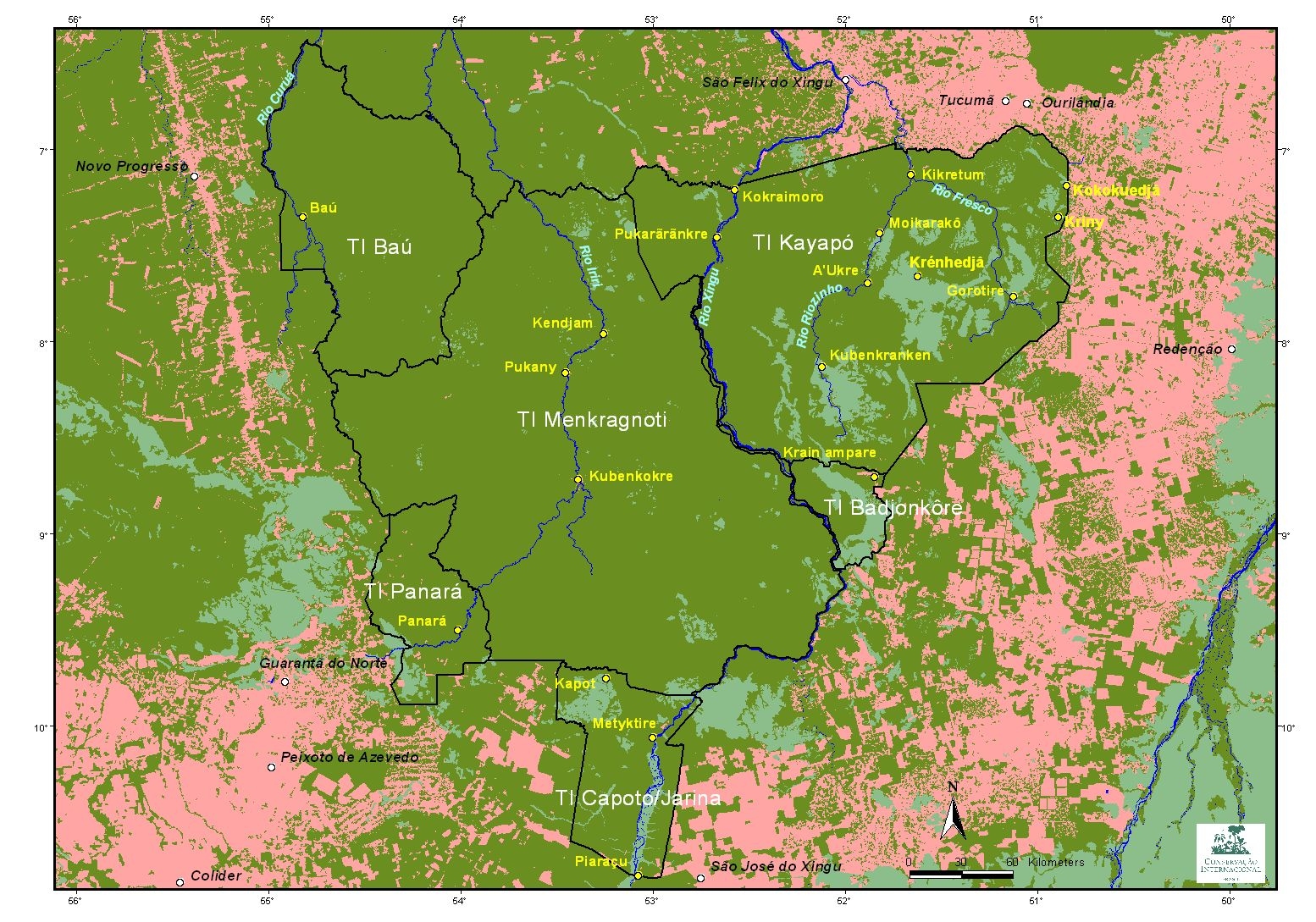

The intact environmental and social conditions of NGO-allied Kayapo territory contrast starkly with the breakdown in the east. As of 2020, the total Kayapo population numbered almost 10,000 people living in 82 communities and small family settlements located throughout their 10.6 million-hectare block of territory. Of this land, 89 percent, or 9,400,000 ha, is controlled by 61% of the Kayapo population who live in 48 communities and small settlements that have allied with the NGOs to pursue sustainable economic autonomy and territorial control. Ninety percent of the approximately 4,000 Kayapo living in 34 communities and small family settlements involved with the illicit frontier economy reside in the 1,200,000-hectare band of eastern territory that fell to the frontier of predatory resource extraction before the arrival of NGOs or before NGO programs were developed enough to help the Kayapo bar the intense wave of illegal activity resurgent in the region after 2010.

|

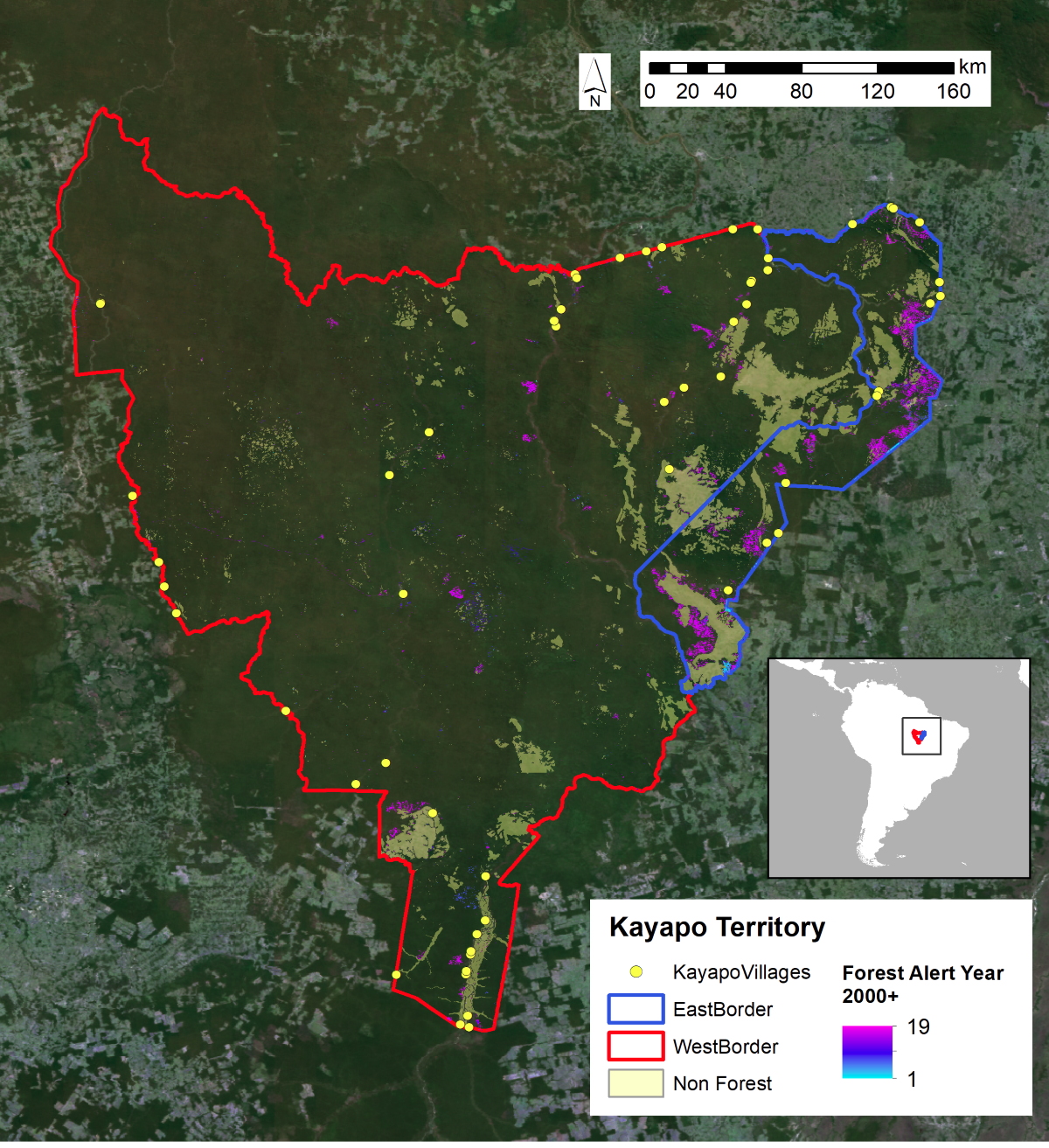

| Figure 1: The block of five contiguous Kayapo indigenous territories (TI) from space (TI Kayapo,TI Bau, TI Mekragnoti, TI Capoto/Jarina, TI Badjonkore). The light colored non-forest in Kayapo territory denotes naturally occurring savanna-woodland on plateaus and outcrops of Brazilian shield rock. The locations of villages with more than 50 people are shown.Red outlines 9.4 million hectares of Kayapo territory that is represented by a local Kayapo NGO and receives outside conservation and development investment. Blue outlines 1.2 million hectares of Kayapo territory that receives no NGO investment. Alerts indicate forest cover loss. |

Deforestation Hot Spots Analysis

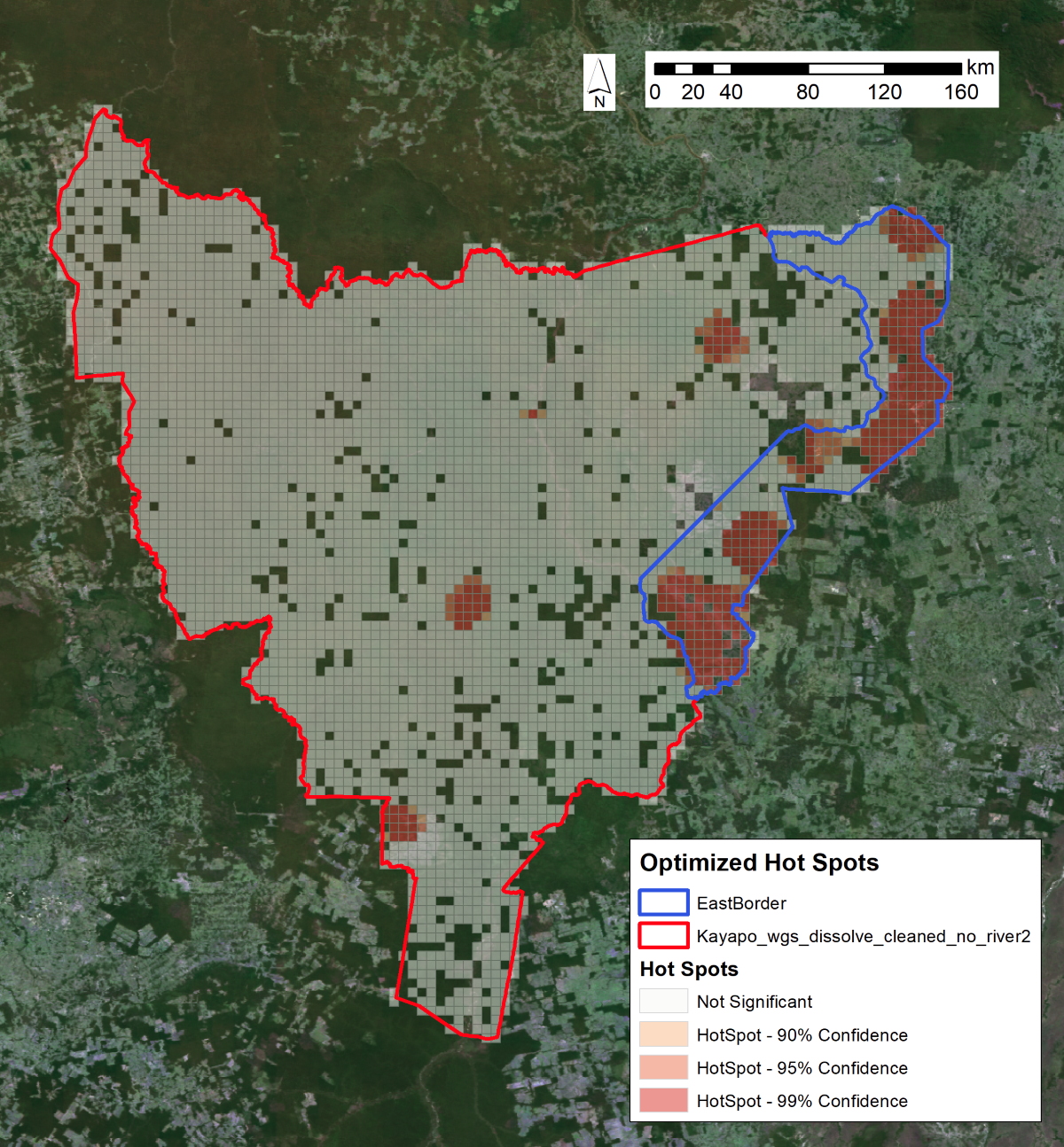

We analysed the Kayapo territory for forest loss events (hotspots) using global forest change 2000-2018 imagery from the Google Earth Engine data catalog and GLAD alert imagery for 2019. From space we observe significant correlation between the location of deforestation hotspots and the presence/absence of NGO investment with Kayapo communities. We see that the eastern zone has much greater densities of loss events per hectare that the NGO-allied western zone.

Deforestation in the Xingu Basin is heavily concentrated outside of the indigenous lands and protected areas. However, the Xingu basin spans the most high-deforestation region of the Amazon frontier. There was a 54% increase in overall deforestation in the Xingu basin during the first two months of 2019 compared with the same period in 2018. Deforestation in indigenous territories increased 158% during the summer of 2019 compared to 2018. Intense activity by illegal loggers and goldminers combined with lack of law enforcement by government authorities has led to significant losses along the eastern band of Kayapo territory. Goldmining and logging continue to expand in the non-NGO represented areas of eastern Kayapo territory. Beginning in about 2015, over 1,500 hectares were being lost annually to goldminers in eastern Kayapo territory.

The relative lack of deforestation and degradation throughout more than 9 million hectares of Kayapo territory to the west compared to the heavily degraded 1.2 million-hectare eastern band of Kayapo territory can be explained by philanthropic investment into Kayapo empowerment for territorial control. Where Kayapo communities receive help to monitor and control their territory, develop equitable and sustainable sources of income and gain insight into threats and options, their borders largely remain secure and forest remains largely intact. Kayapo territory that receives no conservation and development investment is being heavily invaded by goldmining and fire in forest degraded by logging. A low density of hot spot alerts overlaps with Kayapo territory that is represented by and receives program support from Kayapo indigenous NGOs that in turn are supported by international conservation NGOs (Map X). This pattern cannot be explained by cultural differences as the eastern and western Kayapo belong to the same ethnic group whom share the same history; nor can it be explained by distribution of gold and timber which is found throughout Kayapo territory that can be reached from anywhere.

|

|

Figure 2. Hot spot analysis of all forest cover loss events across Kayapo territory from 2001 to 2019. The map shows statistically significant areas of higher hot spot incidence (in red) given the event points. Hot spots indicate deforestation events. |

The Xingu River, a major tributary of the Amazon in Brazil, begins in the semi-deciduous forests and woodland-savannas of Mato Grosso state and flows north for 2,700 km across varying topography before ending in the wet forests of the Amazon near Belem. The Xingu spans major tropical biomes from savanna (cerrado) in the headwaters of the south to semi-deciduous and evergreen wet canopy forests of the southern, mid- and northern regions. More than 20 linguistically differentiated indigenous cultures that hold millennia's worth of ecological knowledge are found in the forests of the Xingu.

During the last four decades, the Xingu has been subject to increasingly intense deforestation as the agricultural frontier inexorably expands north and west. An "arc of fire" constituting the highest rate of deforestation in Brazil and indeed, one of the highest in the world, sweeps across the region. This process of colonization and agricultural expansion, often accompanied by violent land conflict in the lawless frontier, follows road construction, especially the perimetral framework of national highways.

With adequate roads and suitable soils, the Xingu has become an important centre for cattle production (occupying the greatest tracts of land and by far the greatest driver of deforestation), logging (almost all illegal) and production of soybean for export. Dozens of towns have sprung up along roads to support frontier activities and hundreds of thousands of people depend on the frontier economy. In addition, over the last decade a surge in gold prices is driving a wave of illegal and highly destructive goldmining in indigenous and other protected areas.

While this tsunami of forest destruction threatens to engulf the region, an enormous 28.8-million-ha network of protected areas (including both ratified indigenous territories and conservation areas) secures protection in law of 56% of the Xingu basin. This protected area corridor is the great hope for conservation of multi-landscape scale tracts of southeastern Amazonian forest with all its magnificent richness of biodiversity, indigenous cultures and ecosystem services. Indigenous lands of the Xingu are of particular importance because they occupy two thirds of the protected areas corridor and possess de facto protection services - their indigenous inhabitants. Over the past three decades, indigenous territories have proved formidable barriers to forest destruction (Figure 2; see also Nepstad et al., 2006. Inhibition of Amazon deforestation and fire by parks and Indigenous lands. Conservation Biology, 20: 65-73; view pdf)

|

| Figure 2. Satellite image of Kayapó lands and most of the Xingu Indigenous Park (to the south) showing plumes of smoke rising from burning of primary forest remnants outside of the Indigenous Territories. Dark green areas are indigenous lands and light brown areas are ranch and agricultural land. |

However, outside pressure on Kayapó lands continues to increase. If borders are not well monitored in this lawless region of weak governance: ranching, fraudulent land speculation, commercial fishing, logging and goldmining inevitably invade and encroach into protected areas. If they cannot gain clandestine entry, loggers and goldminers will attempt to buy off individual Kayapó to obtain access to the rich timber stocks and gold on their lands. Sometimes they are successful. Once a door is opened, it becomes impossible to control they influx of invaders. When they lack information, insight into foreign capitalist society and sustainable economic alternatives, indigenous peoples are vulnerable to outside pressure to liquidate their resources.

Large infrastructure projects are an increasing threat to the region's remaining forest: i.e., Kayapó land. The mining company Vale S/A operates a nickel mine near Tucuma. The mine has catalyzed immigration to the region, increasing outside pressure on neighbouring Kayapó lands. At the same time, the third largest hydro dam in the world, "Belo Monte" has been built on the Xingu river some 600km upriver from Kayapó lands in Para. To operate efficiently during the dry season, the turbines at Belo Monte will need water released from upriver holding dams -projected for building in Kayapó lands. In the west, the newly paved BR 163 highway from Cuiaba in the south to Santarem in the north has dramatically increased immigration into the region with associated pressure for illegal predatory resource extraction (logging, goldmining) and ranching on western Kayapó lands. Perhaps worst of all, the newly elected far right government of Jair Bolsonaro has vowed to open indigenous lands to industrial development. Strengthening the capacity of Kayapó institutions to protect their boundaries and develop sustainable income alternatives becomes even more crucial in the face of approaching large-scale industry.

Kayapo lands conserve the last remaining large, intact block of native forest in the southeastern Amazon, and maintain the connectivity of this ecoregion with the western Amazon. They confer incalculable benefits to protection of biodiversity, mitigation of climate change and preservation of the crucial role of Amazonian forests in producing rainfall over a much larger geographic scale.

Kayapo territories are large enough to protect large scale ecological processes. For example, very large areas are required to maintain tropical tree species because individuals of species are usually very sparsely distributed. Most tropical tree species depend on co-evolved animal vectors for pollination and seed dispersal across large inter-individual distances - small areas do not contain enough individuals or viable animal vector populations for regeneration over the long term. The intricate web of interdependence among Amazonian species requires large areas for these ecosystems to function and persist.

Kayapo lands remain reasonably undisturbed. Large-bodied game species (including large cracids, lowland tapir, and white-lipped peccary), which are preferred by local peoples throughout the Amazon, are abundant within the hunting range of Kayapo communities. Protected lands in the region safeguard a full complement of disturbance-sensitive wildlife along with an entire vegetation transition from open savanna (cerrado) to close-canopy forests, along with endangered and threatened species (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Threatened vertebrate species found in the Xingu protected areas corridor, with IUCN Red List (2016) designation. Endangered species: Vulnerable or Near Threatened species: |

Kayapó lands and the contiguous Xingu Indigenous Park to the south protect more than four hundred kilometers of the Xingu river from degradation by deforestation, pollution and over-fishing. Preliminary surveys indicate that as many as 1,500 fish species inhabit the Xingu River. Fish are the most important source of protein for local people of the Xingu. Sixteen species of fish are considered endemic to (i.e. only found in) the Xingu.

Our local partners are three Brazilian non-governmental organizations: the Associação Floresta Protegida (AFP), Instituto Kabu (IK), and Instituto Raoni (IR) that together represent all Kayapó communities that form part of the NGO alliance. AFP, IK and IR are pillars of organization for the Kayapó, enabling them to implement programs of conservation and development that strengthen their capacity for territorial control and protection. AFP is based in Tucuma, Para state, and represents communities located east of the Xingu River. IK is based in Novo Progresso, Para, and represents communities located to the north and west of Xingu River. IR, based in Colider, Mato Grosso state, represents communities of the southeast (map of Kayapó territories with names of communities). The Kayapo organizations also collaborate with the Brazilian government Indian agency (FUNAI) responsible for upholding indigenous rights.

Origins of the Kayapo Project

Thanks to the efforts of Canadian tropical ecologist, Barbara Zimmerman, in 1992, Conservation International began working with the Kayapo. With Barbara aa Kayapo Project Director, in the early 2000s, CI helped Kayapo communities to set up their own indigenous NGOs (the three listed above) to build capacity for managing and protecting their territories, which is essential given the lack of government enforcement of indigenous land rights. This was the start of an alliance of the Kayapo with international conservation NGOs that has strengthened of Kayapo territorial surveillance and control as well as developing income generating activities for Kayapo communities.[1]

Since 2007, the informal alliance has included the International Conservation Fund of Canada, Environmental Defense (with funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Kayapo Fund (capitalized by Conservation International and the Brazilian National Development Bank’s Amazonia Fund). There has also been funding from the Amazon Fund, but the contributors to that fund, Norway and Germany, suspended payments in 2019 due to concerns over rising deforestation and the rhetoric emanating from the administration of Jair Bolsonaro. The Kayapo NGOs themselves raise significant program funding from domestic sources, especially from government mandated environmental compensation packages related to road building, mining and the hydro-electric industries. Therefore, ICFC support of high-level functioning of Kayapo NGO administrations leverages significant program support from other sources.

Territorial surveillance and boundary demarcation

Territorial surveillance: ICFC and our US based partner EDF provide surveillance infrastructure and administrative services to Kayapó NGOs including boats, outboard engines, radios, 4X4 vehicles, expedition supplies, fuel, equipment maintenance, accounting and also capacity building workshops. We enable Kayapó NGOs to perform overflight surveillance and ground patrols with the result that several foci of illegal activity have been identified over the years: goldmining, logging and encroachment by ranchers.

Over the past five years, the wave of illegal goldmining, logging, and commercial fishing has been building, using heavy equipment and taking advantage of the expanding network of roads built by ranchers. Sporadic Kayapo border patrol alone proved insufficient to withstand this increased pressure. Government enforcement has always been inadequate, but the Kayapo were able to obtain some helicopter supported enforcement operations to destroy goldmining and logging equipment, and these operations helped to keep the lid partially on invasion. Enforcement of protected and indigenous areas ended in 2019 with the Bolsonaro government and the emboldened invaders stepped up their game.

But a solution exists. The Kayapo NGOs have developed a guard post model that works. The first guard post was installed in 2017 at the northern Xingu river gateway to Kayapo land. Since then, no unauthorized persons gained entry and fish stocks depleted after several years of illegal fishing have rebounded. The success of the Xingu guard post led the Kayapo to set up a second guard post on the Iriri river in the north—a previously remote area now threatened by ranch road development. This guard post protects the Iriri, including a fully established and thriving catch-and-release fly-fishing enterprise for the Iriri river Kayapo in collaboration with company partner Untamed Angling 9UA). With their river protected and fish returning, Kayapo communities of the Xingu are also developing sport fishing with UA and high-end ecotourism to generate sustainable income for their communities.

In 2019 the Kayapo received funding to set up five more guard posts at strategic border locations where loggers and goldminers had begun to gain entry or were threatening to.

Importantly, guard posts generate paid work that benefits all families. Shifts of six men rotate through a guard post every week with the number of shifts allocated to each community in proportion to population size. This equitable distribution of income within and among communities is a powerful antidote to attempts by goldminers and loggers to buy off individuals to gain entry.

Sustainable Income generation

As the frontier of roads and towns consolidated around them, the Kayapo gained much greater access to towns and manufactured goods. The young generation of Kayapo especially seeks technology and education. Today, Kayapo face a choice between unsustainable (illegal) but in the short term high-value activities, and lower-value conservation-based enterprises that take longer to develop but are environmentally and culturally sustainable. All Kayapo in the NGO represented territory continue to choose the latter option. Kayapo NGOs have been developing a successful portfolio of non-timber forest product and service enterprises with their communities that fit with Kayapo culture and that generate equitably distributed benefits. These enterprises are: the harvest and sale of Brazil nut to the domestic food industry; harvest and sale of cumaru nut (tonka bean) to UK cosmetics company “Lush”, international university field courses and internships with the Federal University of Para and US institutional partners, handicrafts sales, and catch-and-release sport-fishing with partner Untamed Angling (see Untamed Angling; Kendjam Lodge; Xingu Lodge).

Sustainable income alternatives are now generating close to half a million dollars per year for Kayapo communities of the NGO alliance. These enterprises continue to grow and develop.

Institution building

Instituto Kabu negotiation with the Ministry of Transportation for highway impact compensation package.

No longer are the traditional warrior tactics of their Kayapo forefathers sufficient for protecting indigenous rights in the 21st century. The Kayapo must learn to protect their interests and rights in the legal context of outside society. Their three NGOs play a central role in their future, hence the value of ICFC's support for management and administration of Kayapó organizations. High functioning administrations have become adept at program development, program implementation and financial accounting, so much so that Kayapó NGOs have been able to obtain the lion's share of program funding on their own.

An important source of program funding accessed by Kayapó NGOs is government mandated environmental compensation packages for infrastructure and industrial development. The AFP Kayapó of the northeast have a deal with the Vale Mining company to compensate for impacts of the nearby "Onça-Puma" nickel mine. Vale funding mitigates mine impacts by supporting the AFP's surveillance and sustainable economic development programs, as well as initiatives to strengthen Kayapó cultural identity. Similarly, the northwestern IK Kayapó receive compensation from the Department of Transportation for impacts of paving the Cuiaba to Santarem BR-163 federal highway. Paving of this highway opened the floodgates to colonization and deforestation along the western border protected by IK and this compensation is playing a crucial role in helping the Kayapó to continue to defend their lands in the west. Negotiation of these significant grants for conservation and development counts on professional level administration performed by the Kayapó NGOs.

Every year, ICFC supports meetings of Kayapó leaders in the Annual General Assemblies of their organizations. At the AGMs, Kayapó leaders review the past year's work and accounts and approve work-plans and budgets for the upcoming year. These meetings are crucial for Kayapo unity of vision and strategic planning in the face of increasing threat.

International Conservation Fund of Canada Copyright © 2009-2025

Registered Canadian charity # 85247 8189 RR0001